Prerequisites: metric spaces

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.1.:}$ (Neighbourhood) Let $X$ be a metric space. A neighbourhood of a point $p$ is a set $N_r(p)$ consisting of all points $q$ such that $d(p,q) < r$. The number $r$ is called the radius of $N_r (p)$.

If we are in an Euclidean metric $(\mathbb{R}^k)$ then,

for $\mathbb{R}^1$ neighbourhoods are segments and for $\mathbb{R}^2$ neighbourhoods are interiors of circles.

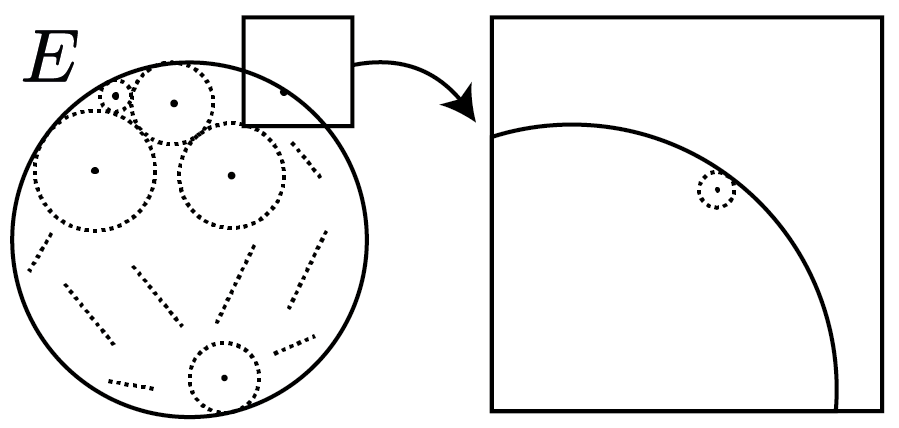

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.2.:}$ (Interior Point) A point $p$ is an interior point of $E$ if there is a neighbourhood $N$ of $p$ such that $N \subset E$.

So to say, $p$ is surrounded by other points of $E$, and not on the “edge” or boundary where points outside of $E$ are arbitrarily close. So for non-interior point we can find a point that is on the “edge” or boundary of the set.

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.3.:}$ (Open Set) $E$ is open if every point of $E$ is an interior point of $E$

To break it down we can say, no matter how “far” a point $p$ is from the “edge” or boundary of $E$, you can always find a neighbourhood $N$ such that $N \subset E$.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.1.:}$ Every neighbourhood is an open set.

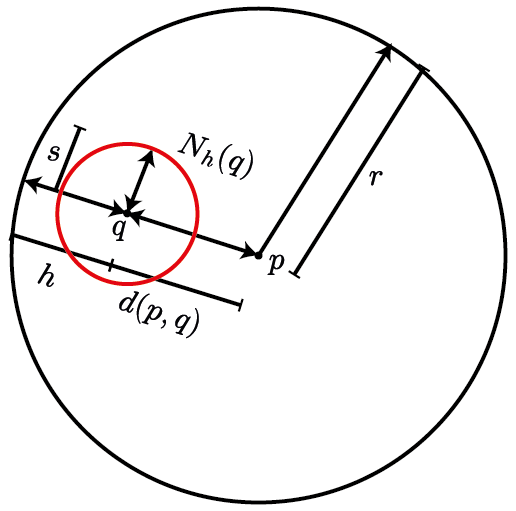

$\textbf{\small Proof:}$ Let us take an arbitrary neighbourhood, say $N_r(p)$. Let $q$ be any point of $E$. Observe that there always exist $h$ such that

since $N_r(p) = \{q : d(p, q) < r\}$. Consider another neighbourhood of $q$ with radius $h$, for any $s$

Using these we can write

means that $s \in N_r(p)$. The point $s$ is inside $N_r(p)$ this works for any $s$ in $N_h(q)$. We also know $s\in N_h(q)$. Hence,

$q$ is an interior point by definition. But $q$ was arbitrary. All points in $N_r(p)$ are interior points making $N_r(p)$ open.

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.4.:}$ (Limit Point) A point $p$ is a limit point of the set $E$ if every neighbourhood of $p$ contains a point $q (\neq p)$ such that $q \in E$

In other words, one cannot isolate the point $p$. In some sense you cannot draw a circle around $p$ (no matter how small) without catching at least one other piece from $E$. $p$ is “clinging” to $E$ so tightly that you cannot separate them with distance. Talking about isolation, we can straightly define “isolated point”

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.4.:}$ (Isolated Point) If $p \in E$ and $p$ is not a limit of the set $E$, then $p$ is called an isolated point of $E$.

To make it solid we will take an example from $\mathbb{R}^1$. Consider the sequence $\frac{1}{n}$. Let $E=\{1,\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \dots\}$. By our very intuition we deduce that $0$ is a limit point of $E$. But let us see whether this intuition is true or not.

- Is $0$ a limit point? Yes, take any neighbourhood around $0$. Then we have

Pick $r = \varepsilon > 0$;

As you might see there are infinitely many $n$ satisfying above inequality.

- Is $1$ a limit point? No, take neighbourhood around $1$ with $r = \frac{1}{10}$.

For $n = 2$, $(1)$ is not satisfied. Thus $1$ is an isolated point.

Also observe that a limit point does not have to be contained in the set itself.

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.5.:}$ (Closed Set) $E$ is closed if every limit point of $E$ is a point of $E$.

To make it concrete we could think the set $E=\{1,\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \dots\} \cup \{0\}$. According to the definition 1.5. set $E$ is closed.

We will state an important theorem about infinity and finiteness criteria for a set.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.2.:}$ If $p$ is a limit point of a set $E$, then every neighbourhood of $p$ contains infinitely many points of $E$

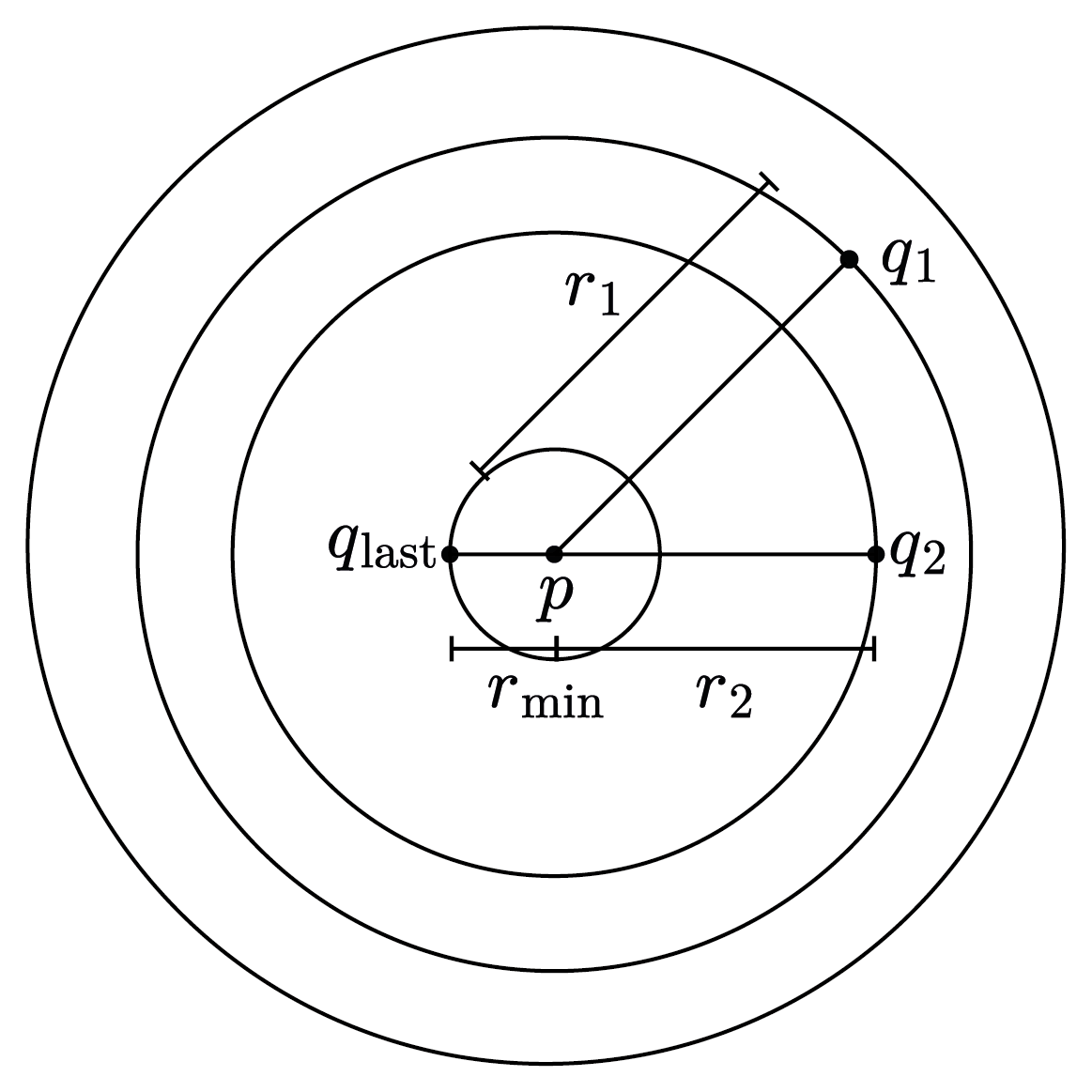

$\textbf{\small Proof:}$ Suppose on contrary there exists a neighbourhood of $p$ that contains finite points of $E$. Say $q_1, q_2, q_3, \dots, q_n$. Let $r = \underset{1 \leq m \leq n}{\min} d(p, q_m) > 0$. Using this minimum $r$ we create a new neighbourhood

However, for this newly created set, the elements are those whose distance $d(p, q_m)$ is smaller than the minimum $r$. But, this is a contradiction because $N_r(p)$ does not contain $q_m$ such that $p \neq q$. By definition $p$ is not a limit point.

As figure (intuitively) shows there is no further elements between minimum distance and $p$.

This theorem yields two corollaries.

$\textbf{\small Corollary 1.1.:}$ A finite set $E$ can never have a limit point.

$\textbf{\small Corollary 1.2.:}$ If a set has a limit point, the set itself must be infinite.