The motivation of this post is to enlarge the steps of theorems and the definition of relativeness, compactness and more. Since the famous and brilliant book Principles of Mathematical Analysis by Walter Rudin is so terse so to say. I love “Baby Rudin”, but unfortunately it is hugely incomprehensible if you do not know what you are doing. Rudin, of course, had deliberately skipped over the details. He probably guessed that the reader was quite gifted in mathematics or the reader is taught by a brilliant teacher.

However, neither I am nor you are genius (well, you are here 😀), and thus understanding what has been said requires details and further steps, which is removed in book. By my nature, I am eager to write and elaborate on everything meticulously, without skipping a beat.

Before starting to read this post you can check this if you are not familiar with (neighbourhoods, open sets, limit points and etc.). We will first start with relative opennes and continue with compactness.

I will start with relative opennes. From our very heuristic instinct we can find the definition of relative opennes by ourselves. Well by just “words” we can start thinking to find relationship “relative opennes” and “opennes”. Not to distract but for those who interested in words and relations one can search Gottlob Frege

The concept of relative opennes is the specialization of opennes by defining exactly the same thing with smaller subsets.

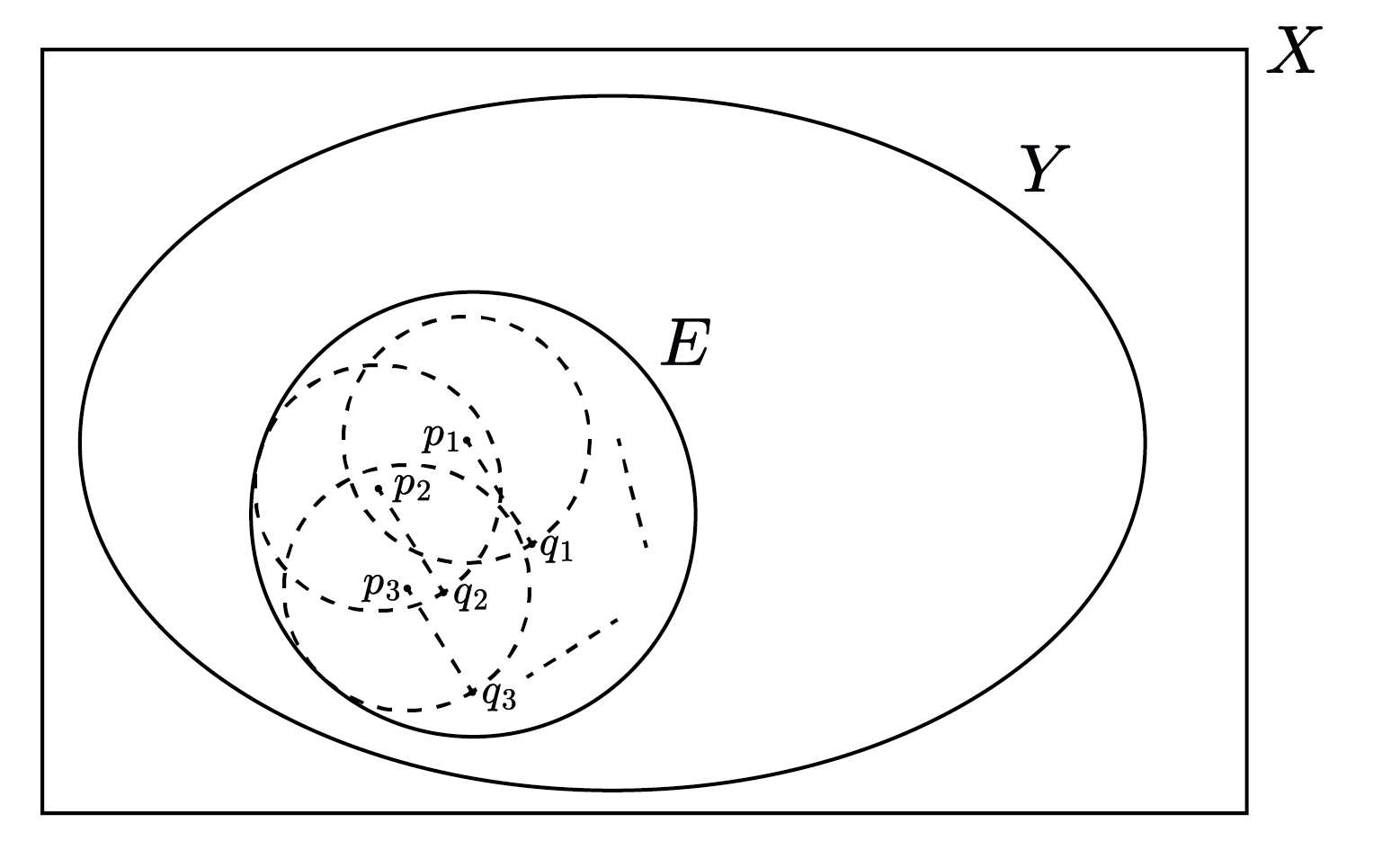

Let $X$ be a metric space and $E \subset Y \subset X$. We say $E$ is open relative to $Y$ if for every point $p$ of $E$ there exists a radius $r>0$ such that all points $q$ which are in $Y$ and satisfy $d(p,q)<r$ are also in $E$.

Observe that the definition of open set requires a neighbourhood $N$ such that $N\subset E$. However, for relative opennes only requires $\{q \in Y : d(p,q)<r\} \subset E$ we do not care about points in $X \backslash Y$ (points in X and not in Y).

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.1.:}$ Suppose $Y \subset X$. A subset $E$ of $Y$ is open relative to $Y$ if and only if $E = Y \cap G$ for some open subset $G$ of $X$.

$\textbf{\small Proof:}$ ($\Rightarrow$) Suppose $E$ is open relative to $Y$. Choose a radius $r_p$ such that all points in $Y$ that are with distance $r_p$ of $p$ are also in $E$. And define $V_p$ as follows:

this implies $q \in E$. No we define a set $G$

$G$ is open set of $X$, because every $V_p \subset X$ and for any collection of open sets $\{V_p\}$, $\bigcup V_p$ is open.

Observe, $p \in V_p$ for all $p \in E$. Therefore, $p \in G$ and $p \in Y$. Thus

By the choice of $r_p$ the intersection of any ball $V_p$ with $Y$ is contained in $E$. Thus $Y \cap V_p \subset E$ and $Y \cap G \subset E$. This implies $E = Y \cap G$.

($\Leftarrow$) Let $G$ be an open set in $X$ and $E = Y \cap G$. Take $p \in E$, since $E \subset G$, $p \in G$. $G$ is open, thus there exists a neighbourhood $V_p \subset G$. And $V_p \cap Y$ contains points that are in both $G$ and $Y$. These points are in $E$ because $E = Y \cap G$. This satisfies the definition of relative opennes: $p$ has a neighbourhood relative to $Y$ that stays inside in $E$.

$\text{\small Example: }$ Let $X = \mathbb{R}$, $Y = [0,1]$, $E = [0, 0.5)$. Is $E$ open? No, because if we take neighbourhood $(-\varepsilon + 0, \varepsilon + 0) \not\subset E$. However, it is open relative to $Y$ because

$G$ is open and

We shrink the galaxy, that the set $E$ live in, to the $[0,1]$ and thus the problem with the edges is vanished.

Now, let us move to the concept of compact sets. But first we will give two important definitions

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.1.:}$ (Open Cover) Open cover of a set $E$ in a metric space $X$ we mean a collection $\{G_{\alpha}\}$ of open subsets of $X$ such that $E \subset \bigcup_{\alpha} G_{\alpha}$.

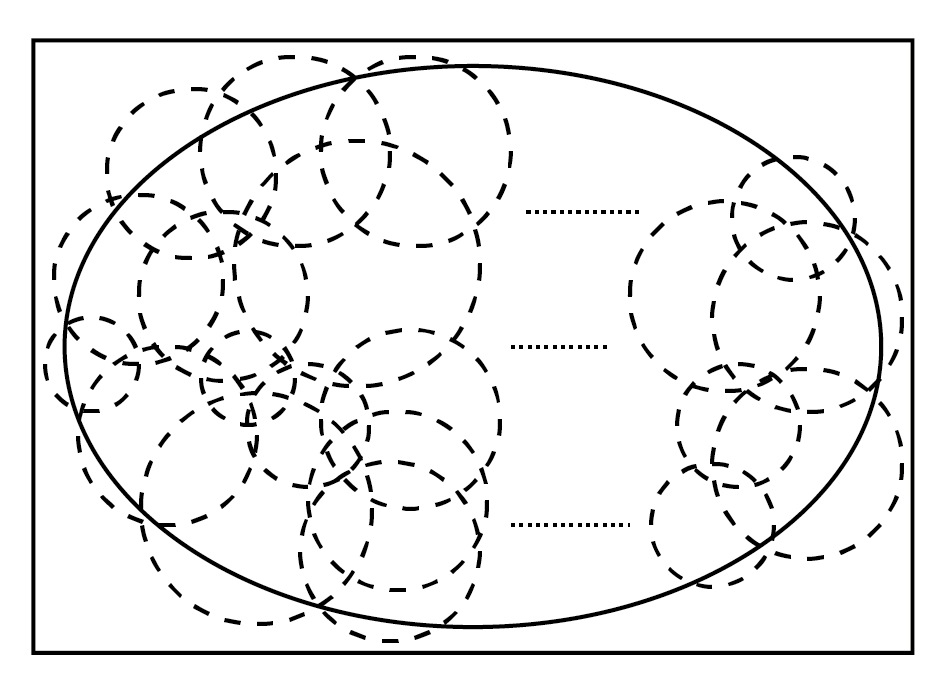

We have the union of infinitely many open sets that covers the E. The following figure shows what could it look like to form a open cover. Remember that, I have limited technology to depict infinity. Therefore, think these open sets as if they are infinitely many. However, mathematicians also thought about it, and as a result they made up finite subcover.

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.2.:}$ (Finite Subcover) A subset $K$ of a metric space $X$ is said to be compact if every open cover of $K$ contains a finite subcover.

You start with a collection of open sets that cover $K$. The test is whether you can throw away all but a finite number of them and still cover $K$

Intuitively, a compact set is the “next best thing to a finite set”.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.2.:}$ Suppose $K \subset Y \subset X$. Then $K$ is compact relative to $X$ if and only if $K$ is compact relative to $Y$.

$\textbf{\small Proof:}$ ($\Rightarrow$) Suppose $K$ is compact relative to $X$, and let $\{V_{\alpha}\}$ be a collection of sets, open relative to $Y$, such that $K \subset \bigcup_{\alpha} V_{\alpha}$ ($V_{\alpha}$ is an open cover of $K$). Since $V_{\alpha}$ is open relative to $Y$, there exist an open subsets $G_{\alpha}$ of $X$ such that

Then we can write

and therefore

We know $K$ is compact relative to $X$, therefore there exists a finite subcover

Since $K \subset Y$ we have

This shows $K$ is compact relative to $Y$.

($\Leftarrow$) Suppose $K$ is compact relative to $Y$, and let $\{G_{\alpha}\}$ be a collection of open subsets of $X$ such that $K \subset \bigcup_{\alpha} G_{\alpha}$. Define sets $V_{\alpha}$ open relative to $Y$, means there exists $G_{\alpha}$ such that

$K \subset Y$ and $K\subset \bigcup_{\alpha} G_{\alpha}$ thus $K\subset \bigcup V_{\alpha}$. By assumption, $K$ is compact relative to $Y$. Thus $K\subset V_{\alpha_1} \cup V_{\alpha_2} \cup \dots \cup V_{\alpha_n}$. $V_{\alpha} \subset G_{\alpha}$ is trivial. This implies,

Corresponding finite number of $G_{\alpha}$ sets also covers $K$.