Why to use differential equations

I do not and will not like giving plain formula or technic to solve problem, rather I want to learn the truth as Faust did. Faust was extremely successful person, he was some kind of researcher, he read and read. However, he was not satisfied with the position of his life. It seemed meaningles and pointless to him. One day he made a pact with Mephistoteles. The deal was pretty straightforward: in exchange for his soul he will gain unlimited knowledge and hedonic pleasures. If Faust had been a real person, he would have hated plain formulas given without reasoning. Therefore, we will not use any formula, theorem or lemma without proving it beforehand. I have briefly discussed Faust here.

Derivative or instantaneous rate of change

Whenever I thought about derivatives, I thought of rate of change of something. It could be heat on the some surface, it could be my velocity, it could be anything else. We have not formally proved the derivatives, but we will prove them in the Analysis section follow here. For now, it is enough to visualize and understand the concept. Take for example below graph:

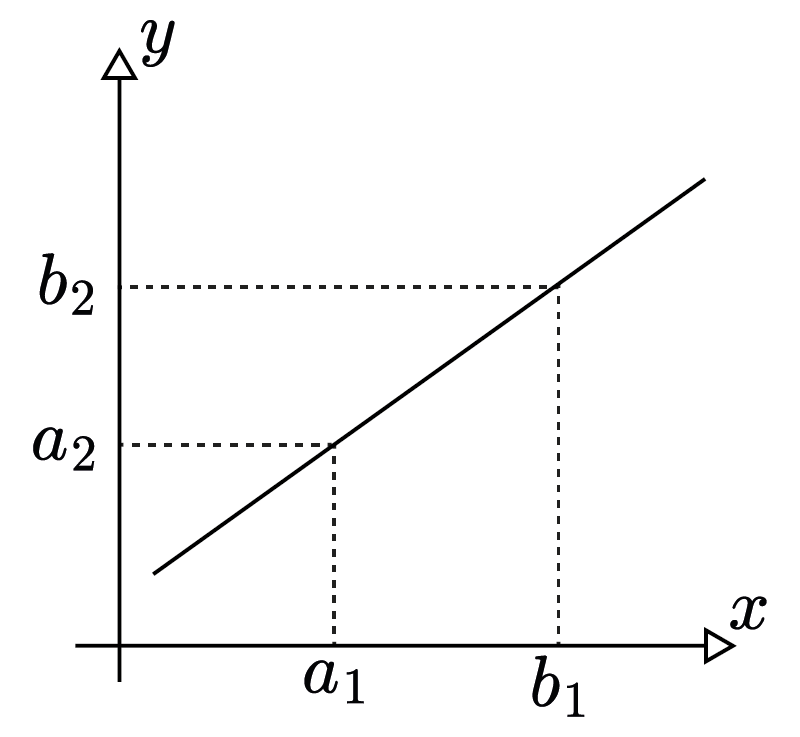

Here we see a anonymous graph with $x-y$ coordinate. Let us choose two values from $x$-axis and two corresponding values from $y$-axis. At the end we would get the following:

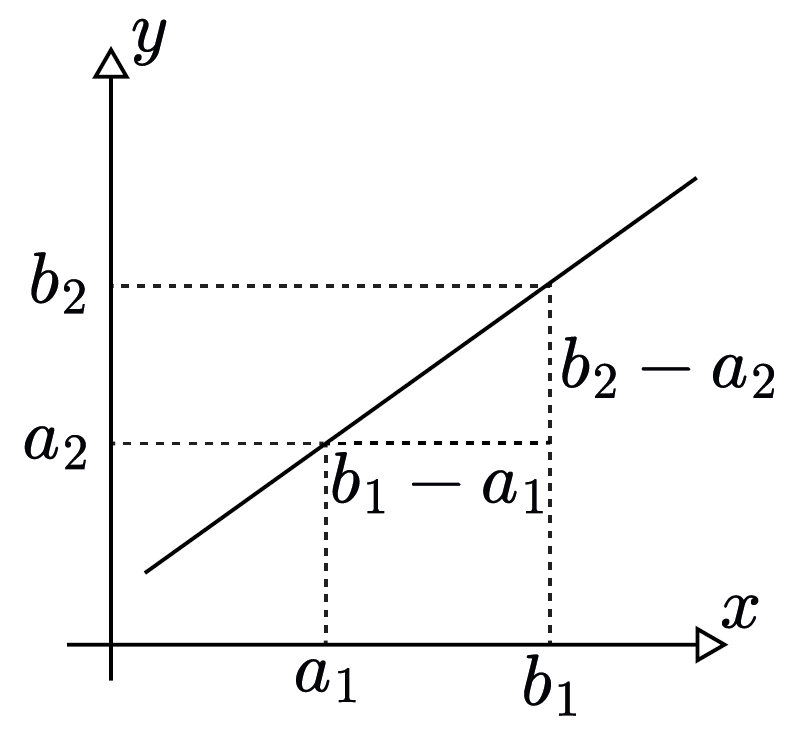

And if we measure the distances between the selected points we would get $b_1-a_1$ and $b_2 - a_2$. Observe that to calculate the rate of change of the values on $y$-axis with respect to the values on $x$-axis we should calculate the slope of the graph at those particular points. We have an independent variable $x$ that changes by an amount $\Delta x = b_1 - a_1$. We have a dependent variable $y$ that changes by an amount $\Delta y = b_2 - a_2$. The average rate of change is defined as the ratio of this change. We call this ratio $m$. Therefore: $m = \dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \dfrac{b_2 - a_2}{b_1 - a_1}$.

To formulate it, we take $f(x):\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ and $a_1,b_1 \in \mathbb{R}$ where $b_1-a_1 \neq 0$. We write the average rate of change for a function $f(x)$ over the interval $[a_1,b_1]$ is given by $\dfrac{f(b_1)-f(a_1)}{b_1-a_1}$, where $f(a_1) = a_2$ and $f(b_1) = b_2$.

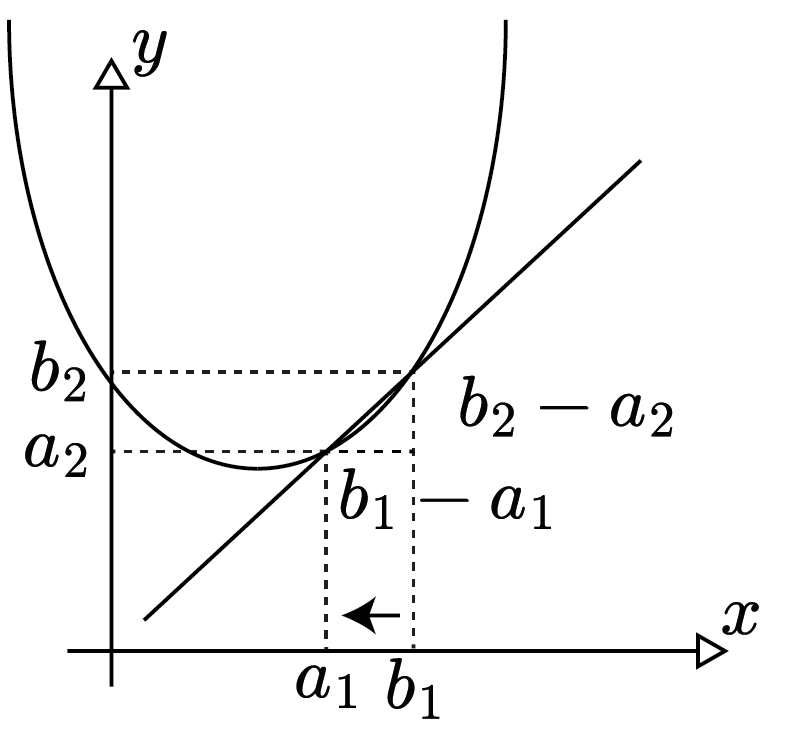

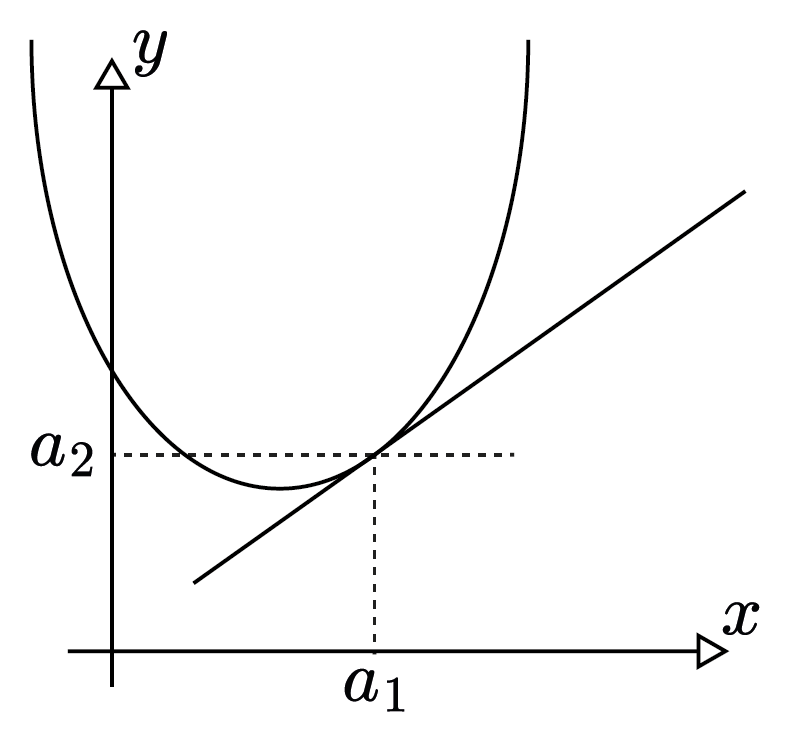

But, as you might notice on the straight line, the rate of change is constant, once you found the slope you stick to it and use it everywhere. The questions arise: What if we want to find the slope of the curve? What happens to that ratio, $\dfrac{f(b_1)-f(a_1)}{b_1-a_1}$, as the interval $[a_1, b_1]$ shrinks? What happens when $b_1$ gets infinitesimally close to $a_1$? Infinitesimal is familiar from the Analysis section. Let us examine the graph below:

As the distance between the two points on the $x$-axis decreases, observe that the two points appear to merge together. In other words, as $b_1$ approaches $a_1$, the interval $\Delta x$ shrinks towards zero, so that we get a point-wise slope of the graph at the point we approach. We call it instantaneous rate of change. More rigorously, “instantaneous rate of change at the point $a_1$” = $\displaystyle\lim_{b_1 \rightarrow a_1}\dfrac{f(b_1)-f(a_1)}{b_1-a_1}$. We generally use this formula to calculate the slope of a tangent line, which is a limit of a secant line pivots. Namely, derivative of a function. Following graph shows the idea of tangent curve and the corresponding slope at selected point:

I prefer to write derivatives in the form of $f^{\prime}(x)$, $f^{\prime \prime}(x)$,… etc. But the form $\dfrac{dy}{dx}$, $\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\right)$,… etc. is also valid. The slope at some point produces an angle of corresponding tangent line. By a little deduction we can infer that the angle reads the direction of the curve, whether it is decreasing or increasing.

The unreachable consensus

The derivative, as the central part of calculus, was formalized independently by two men in the late 17th century. The credit for its discovery is shared by: Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Newton began his work in the mid-1660s during the plague years. His motivation was physics. He needed to describe motion, velocity, and acceleration. Leibniz developed his version of calculus about a decade later, in the mid-1670s. His motivation was more philosophical and geometric. He was obsessed with finding a universal symbolic language for reason and focused on the geometry of tangent lines.

What is differential equations exactly?

Differential equations are the language of nature. They are used to create a mathematical model of a system that changes. We often don’t know the exact function that describes a system, but we do know the rules that govern its change. We write those rules down as a differential equation. Solving the equation reveals the function. In short, the differential equation describes a relationship between the quantity that is continuously varying with respect to the change in another quantity. Solving it gives you the function for the quantity itself.

Real-life examples

When you are driving, your speedometer does not show your average speed. It shows your instantaneous velocity. It is a derivative-measuring machine. It answers the question, “How fast is my position changing at this exact second?”. We observe that force ($F$) causes an object’s velocity to change (acceleration, $a$).

Derivatives:

- Velocity: $v(t) = \frac{dx}{dt}$ (derivative of position $x$)

- Acceleration: $a(t) = \frac{dv}{dt} = \frac{d^2x}{dt^2}$ (second derivative of position)

Differential Equation (The Law):

- $F = ma \implies F = m \frac{d^2x}{dt^2}$

The Solution (The Function):

- Solving this DE gives you $x(t)$, the object’s path of motion. The solution is well-known function from high school: $x(t)=x_0+v_0t+\dfrac{F_0}{2m}t^2$, where $x_0$ and $v_0$ are initial conditions and $F_0$ is the magnitude of the constant force applied.

Heat on a surface. “How fast does the temperature drop per inch as I move away from the source?” A steep gradient ($T’(x)$ is a large negative number) means the heat is dissipating quickly. This derivative governs everything from heat sink design in your computer to materials science in a jet engine. Temperature Function ($T(x)$): the temperature at a distance $x$ from a heat source. Derivative ($T’(x)$): the temperature gradient.

In the next sections, we will try to solve different types of differential equations. And when possible, we will give real-life examples for each differential equations.