The converse of Theorem 1.2. (every convergent sequence is bounded) is not generally true. For example, observe the sequence $\left((-1)^n\right)_n$. The elements of these sequence consist only of $1$ and $-1$. It is bounded, yet not convergent. So we have a very great example of disproving a theorem by a counterexample. I love such examples because it is not important how big the theorem is, if you can find any counterexample then you can either throw that theorem into thrash bin or you can refine and redefine it. What we will do right now is refining and redefining. To do so, we need definition for monotonicity.

Monotonicity

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.15.:} $ (Monotone Sequence) A sequence $(a_n)$ is increasing if $a_n \leq a_{n+1}$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and decreasing if $a_n \geq a_{n+1}$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$. A sequence is monotone if it is either increasing or decreasing.

There are ways to infer that a sequence is whether increasing or decreasing. We can either use difference between successive terms:

- If $a_{n+1} - a_n \geq 0$, then we say increasing

- If $a_{n+1} - a_n \leq 0$, then we say decreasing

The other way we can use is checking the ratio between successive terms:

- If $\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} \geq 1$, then we say increasing

- If $\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} \leq 1$, then we say decreasing

$\textbf{\small Example:}$ Decide whether the sequence $\left(\dfrac{1}{n}\right)$ is decreasing or increasing.

$\textbf{\small Solution:}$ Take $a_n = \dfrac{1}{n}$ and $a_{n+1} = \dfrac{1}{n+1}$. Using above instructions we have:

$\dfrac{1}{n+1} - \dfrac{1}{n} = \dfrac{n - n - 1}{(n+1)n} = - \dfrac{1}{n^2+n} < 0$. So this sequence is strictly decreasing.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.6.:} $ (Monotone Convergence Theorem) If a sequence is monotone and bounded, then it converges

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ Let $(a_n)$ be monotone increasing and bounded sequence. In other words, there exists $s$ such that $\vert a_n \vert \leq s$, $\forall n \in \mathbb{N}$ $(1)$. Also monotonicity reads $a_n > a_N$, $\forall n > N$ $(2)$.

By $(1)$ we write $s = \sup{a_n}$. Since $s$ is LUB, $s - \epsilon$ is not an upper bound (if so $s-\epsilon$ would be LUB), so there exists a point in the sequence $a_N$ such that $s-\epsilon < a_N$. By using $(2)$ we have:

$$s-\epsilon < a_N \overset{\text{(2)}}{\leq} a_n \overset{\text{(1)}}{\leq} s < s + \epsilon$$

Therefore, $\vert a_n - s \vert < \epsilon$ as desired.

Think of any sequence, by using our intuition (which is a dangerous weapon) we could make up a definition called subsequence. Basically, we take a base sequence and then specifically choose elements from it to create a new sequence.

Subsequences

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.16.:} $ (Subsequence) Let $(a_n)$ be a sequence of real numbers, and let $n_1 < n_2 < \dots < n_{k-1} < n_k < \dots$ be an increasing sequence of natural numbers. Then the sequence $$(a_{n_1}, a_{n_2}, a_{n_3}, \dots)$$ is called subsequence of $(a_n)$ and is denoted by $(a_{n_k})$, where $k \in \mathbb{N}$ indexes the subsequence.

For instance, take $(a_n)=(1, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \dots)$. Let $n_1 < n_2 < n_3 < \dots < n_k < \dots$ be the increasing sequence of natural numbers defined by $n_k = 2k$. Thus, $n_1 = 2$, $n_2 = 4$, $n_3 = 6$, $\dots$ This reads $a_{n_1} = a_2 = \frac{1}{2}$, $\dots$ So that we can built the subsequence $(a_{n_k})_k = (\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{4}, \frac{1}{6}, \dots)$. However, we cannot say that the following sequence $(\frac{1}{5}, \frac{1}{100}, \frac{1}{10}, \frac{1}{20}, \dots)$ is a subsequence of $(a_n)$, because it does not obey the order of the base sequence.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.7.:} $ If $(a_n)$ converges then all subsequence of $(a_n)$ converges to the same number.

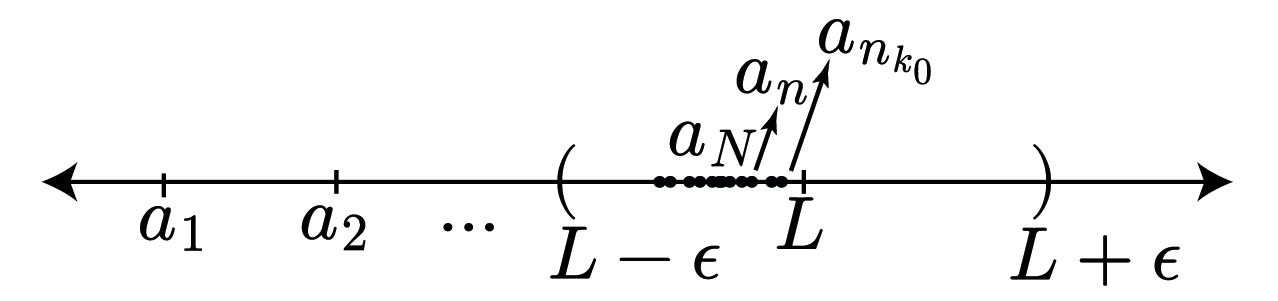

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ Let $(a_n)$ converges to $L$, means for any $\epsilon > 0$ there exists $N(\epsilon)$ such that $\vert a_n - L \vert < \epsilon$, $\forall n > N$. At a very thorough level, we can say that after some $n$th index the difference between the element at the $n$th index $(a_n)$ and $L$ decrease. So we choose a number $k_0 \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n_{k_0} > N$, then we also have the same inequality for the subsequence as long as $n_{k_0} > N$. Below image refer to the Theorem 1.7.

Now, we will give a very powerful theorem for subsequences. It is as natural as $1+1=2$.

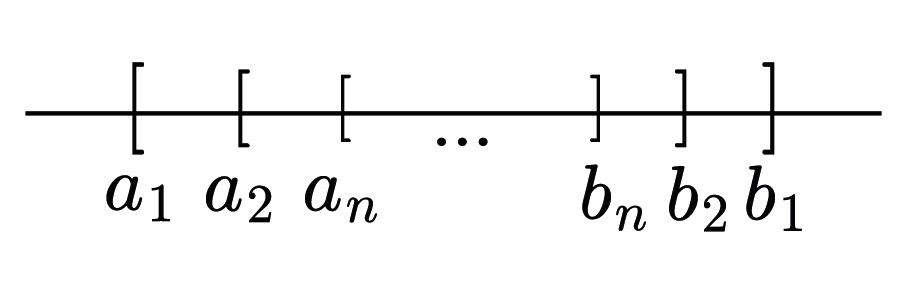

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.8.:} $ (Nested Interval Theorem) If $I_n = [a_n, b_n]$, $n=1,2,3,\dots$ is a set of nested intervals such that $I_1 \supset I_2 \supset \dots$ and $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} (b_n-a_n) = 0$, then $(I_n)$ converges to a exactly one unique point.

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ We know that $I_n=[a_n, b_n]$ forms nested interval, means that $(a_n)$ is increasing and $(b_n)$ is decreasing sequences. Since $a_1 \leq a_n \leq b_1$ and $a_1 \leq b_n \leq b_1$ are satisfied we can directly use monotone convergence theorem. Let $\lim a_n = a$ and $\lim b_n = b$. The theorem states that $I_n$ converges to a unique number and to show this, it is enough to demonstrate $a=b$.

Let $\epsilon > 0$ be given. We know the followings:

- $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} a_n=a \iff \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists N_1 = N_1(\epsilon) : \forall n > N, \vert a_n - a \vert < \epsilon/3$

- $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} b_n=b \iff \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists N_2 = N_2(\epsilon) : \forall n > N, \vert b_n - b \vert < \epsilon/3$

- $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} a_n=b_n \iff \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists N_3 = N_3(\epsilon) : \forall n > N, \vert a_n - b_n \vert < \epsilon/3$

Let $N=\max\{N_1, N_2, N_3\}$. Then $\forall n > N$ we have:

$\vert b-a\vert = \vert b - b_n + b_n - a + a_n - a_n \vert < \vert a_n-a \vert +\vert b_n-b \vert +\vert a_n-b_n \vert < \epsilon$

Look closely to the inequality, we end up with $\vert b - a\vert < \epsilon$, but we also know $\epsilon > 0$. So only way out is $\vert b-a \vert = 0$.

This theorem reads there is no gap in the $\mathbb{R}$, which let us say $\mathbb{R}$ is complete and $\mathbb{Q}$ has gaps. Because notice that if we apply this theorem on $\mathbb{Q}$, we would have $\sqrt{2}$ as an intersection point and we know that $\sqrt{2} \notin \mathbb{Q}$. Now, using Theorem 1.8, we will prove Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem.

Bolzano - Weierstrass Theorem

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.9.:} $ (Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem) Every bounded sequence contains a convergent subsequence.

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ Let $(a_n)$ be a bounded sequence. By using the Definition 1.9 from 3rd part. We have an interval $[-M, M]$, which contains the elements of the $(a_n)$. Using this closed interval we can create subintervals. By the pigeonhole principle, we can assume that one of the closed intervals has infinitely many terms of the sequence $(a_n)$. Let this interval be $[a_1, b_1]$.

We will employ the Nested Interval Theorem. The construction proceeds as follows:

Construction: Divide $I_1 = [a_1, b_1]$ into two equal sub-intervals. By the pigeonhole principle, at least one of these closed intervals must contain infinitely many terms of the sequence $(a_n)$. Let this interval be $I_2 = [a_2, b_2]$.

Induction: Repeating this process inductively, we obtain a sequence of nested closed intervals $I_1 \supseteq I_2 \supseteq \dots \supseteq I_n \supseteq \dots$ such that each $I_n$ contains infinitely many terms of $(a_n)$.

Length analysis: Observe that the length of each interval is given by $b_n - a_n = \frac{b_1 - a_1}{2^{n-1}}$. Consequently,$$\lim_{n \to \infty} (b_n - a_n) = 0.$$

Since $(I_n)$ is a sequence of nested closed intervals whose lengths converge to zero, the Nested Interval Theorem implies that their intersection contains exactly one unique point, say $L$. That is, $\bigcap_{n=1}^{\infty} I_n = {L}$.

There is one more step: we need to find a subsequence that converges to $L$. Choose $x_{n_1} \in [a_1, b_1]$, $x_{n_2} \in [a_2, b_2]$. Since $I_2$ contains infinitely many terms of the sequence, there exists an index $n_2 > n_1$ such that $x_{n_2} \in I_2$.

Similarly, $x_{n_3} \in [a_3, b_3]$, $x_{n_4} \in [a_4, b_4]$ where $n_4 > n_3$. Hence, we obtain subsequence $(x_{n_k})$ of $(x_n)$ such that

$$a_k \le x_{n_k} \le b_k \quad \text{for all } k \in \mathbb{N}.$$

Using squeeze theorem from part 5 and recall that $\lim_{k \to \infty} (b_k - a_k) = 0$:

$$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} x_{n_k} = L$$

We can prove Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem using Axiom of Completeness. Consider the following exercise:

Another proof to BW

$\textbf{\small Exercise:} $ Let $(a_n)$ be a bounded sequence, and define the set $S=\{x \in \mathbb{R} : x < a_n$ for infinitely many terms $a_n \}$. Show that there exists a subsequence $(a_{n_k})$ converging to $s=\sup S$.

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $

We should show there exists supremum of S, namely $\sup S$. Observe that $S$ is not empty. Since $(a_n)$ is bounded there exists a lower bound $L$ such that $L \leq a_n$ for all $n$. Consider the number $L-1$. Since $L - 1 < a_n$ for all $n$ (which is infinitely many), $L - 1 \in S$. $S$ is bounded above. Since $(a_n)$ is bounded, there exists an upper bound $M$ such that $a_n \le M$ for all $n$. By the Axiom of Completeness, since $S$ is a non-empty set of real numbers bounded above, the supremum $s=\sup S$ exists.

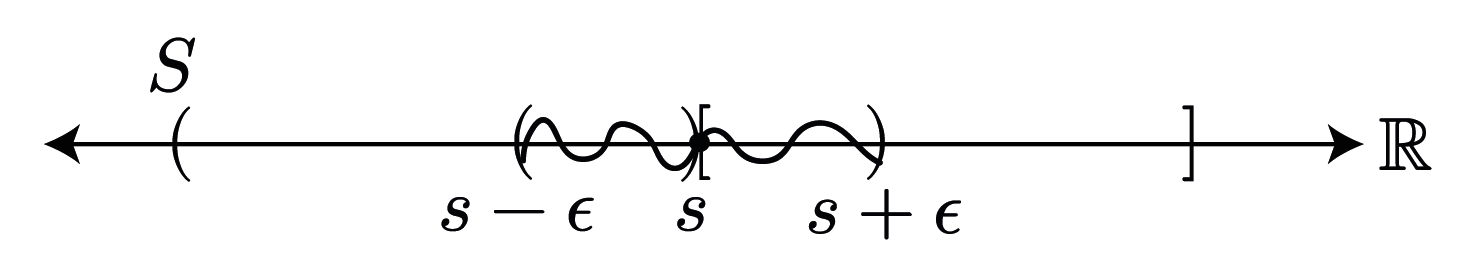

Consider the following real line:

We consider the marked area. There we create an $s$-neighbourhood. Now, we have two different outputs for this neighbourhood.

Consider the point $s-\epsilon$. Notice that $s-\epsilon$ is not an upper bound (if so, it would be LUB). Since it is not an upper bound there exist $x$ such that $x > s-\epsilon$. Also by definition of $S$ we know $a_n > x$. Thus, $a_n > x > s - \epsilon$ satisfied for infinitely many n.

Consider the point $s+\epsilon$. Since $s+\epsilon > s$ and $s$ is the supremum, $s+\epsilon \notin S$ (a number ($s+\epsilon$) greater than $s$ cannot be contained in S). In other words, $a_n > s +\epsilon$ is satisfied for only finitely many terms.

Combining these two would read the interval $(s-\epsilon, s+\epsilon)$ has infinitely many terms.

We will define $a_{n_k}$. Let $\epsilon = 1$. Then, there are infinitely many terms in $(s - 1, s + 1)$. Choose $n_1$ such that:

$$ \begin{aligned} s-1 < a_{n_1} &< s+1 \\ \vert a_{n_1} - s\vert &< 1 \end{aligned} $$

Similarly, since there are infinitely many terms in $(s-\frac{1}{2}, s+\frac{1}{2})$ choose $n_2$ such that $n_2 > n_1$ and:

$$ \begin{aligned} s-\frac{1}{2} < a_{n_2} &< s+\frac{1}{2} \\ \vert a_{n_2}-s\vert &< \frac{1}{2} \end{aligned} $$

Assume we have chosen indices $n_{k-1} > \dots > n_2 > n_1$. Let $\epsilon = \frac{1}{k}$. There are infinitely many terms $a_{n_k}$ satisfying

$$s-\frac{1}{k} < a_{n_k} < s+\frac{1}{k}$$

and we are certain that we can find $n_{k} > n_{k-1}$ that satisfies

$$\vert a_{n_k} -s \vert < \frac{1}{k}$$

Last step is to prove convergence. Let $\epsilon > 0$ be given, there exists $N(\epsilon) > \lfloor{\epsilon} \rfloor$ such that:

$$\vert a_{n_k} - s\vert$$

For all $k > N$ we have:

$$\vert a_{n_k} -s \vert < \frac{1}{k} < \frac{1}{N} < \epsilon$$

Thus, by definition of convergence, the subsequence $a_{n_k}$ converges to $s$.

Cauchy ❤️

Cauchy convergence let us decide whether a given sequence is convergent or not regardless of knowing limit. The Cauchy Criterion acts as a detector that says: “I don’t know exactly where this is going, but I guarantee it has arrived somewhere.”

$\textbf{\small Definition 1.17.:} $ (Cauchy Sequences) A sequence $(a_n)$ is Cauchy sequence if $\epsilon > 0$, $\exists N=N(\epsilon)$ such that $\vert a_n - a_m\vert < \epsilon$, $\forall n,m > N$

So we take the terms at $n$th index and $m$th index from sequence $(a_n)$ and look at the difference.

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.10.:} $ Cauchy sequences are bounded

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ Let $(a_n)$ be a Cauchy sequence then $\forall \epsilon > 0$, $\exists N$ such that $n,m > N$ such that $\vert a_n-a_m \vert < \epsilon$. Choose $n_0 > N$. Then $\vert a_n\vert = \vert a_n -a_{n_0} + a_{n_0}\vert \leq \vert a_n - a_{n_0}\vert + \vert a_n \vert < \epsilon + \vert a_{n_0}\vert$, $\forall n > N$.

Let $N=\max\{\vert a_1\vert, \vert a_2 \vert, \dots, \vert a_N \vert, \dots, \vert a_{n_0} + \epsilon \vert, \dots\}$. $\vert a_n \vert \leq M$. Hence, $(a_n)$ is bounded

Theorem 1.10 will lose its magic after proving the Cauchy Criterion. Because it says whatever valid for convergent sequences is also valid for Cauchy sequences (in complete spaces ofc).

$\textbf{\small Theorem 1.11.:} $ (Cauchy Criterion) A sequence is converges if and only if it is a Cauchy sequence

$\textbf{\small Proof:} $ $(\Rightarrow)$ Let $(a_n)$ be a convergent sequence and $\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} a_n = a$. Given $\epsilon > 0$, $\exists N$ such that $\vert a_n - a\vert < \frac{\epsilon}{2}$, $\forall n > N$. Choose $n, m > N$. Then,

$$ \begin{aligned} |a_n - a_m| &= |a_n - a + a - a_m| \\ &\leq \overbrace{|a_n - a| + |a_m - a|}^{\text{Triangle Inequality}} \\ &< \epsilon \end{aligned} $$

Thus, $(a_n)$ is a Cauchy sequence.

$(\Leftarrow)$ Let $(a_n)$ be a Cauchy sequence. Then, given $\epsilon > 0$, $\exists N(\epsilon)$ such that $\vert a_n - a_m\vert < \frac{\epsilon}{2}$ for all $n, m > N$. By theorem 1.10 the sequence $(a_n)$ is bounded, and by theorem 1.9 (Bolzano - Weierstrass) $(a_n)$ contains a convergent subsequence, say $(a_{n_k})$. Let $\epsilon > 0$ be given, then there exists $N(\epsilon)$ such that $\vert a_{n_k} - a\vert < \frac{\epsilon}{2}$ for all $k > N$.

To sum up and devise everything, let $\epsilon > 0$ be given. If $n > N$ then,

$$ \begin{aligned} |a_n - a| &= |a_n - a_{n_k} + a_{n_k} - a| \\ &\leq \overbrace{|a_{n_k} - a_n|}^{\text{Cauchy Sequence}} + \overbrace{|a_{n_k} - a|}^{\text{By Definition}} \\ &< \frac{\epsilon}{2} + \frac{\epsilon}{2} = \epsilon \end{aligned} $$

Hence, $\vert a_n - a\vert <\epsilon$.

We have reached the end of this exploration. I believe this stands as the most significant post I have written on this blog to date. We have not only uncovered powerful, elegant, and fundamental theorems but also sharpened our logical toolkit. From direct constructions to proofs by contradiction, the techniques we applied here are the bedrock of Real Analysis. We will carry these tools forward as we dive into deeper topics in the future. Until the next post 👋.